John Laming AFC has kindly contributed this account of Ag Flying in Tiger Moths during the 1950’s:

“In 1955, with the rank of Pilot Officer, I was based at RAAF No 1 Basic Flying Training School, Uranquinty, 14 miles from Wagga Wagga NSW. I was one of about twenty flying instructors at the flying school. The Commanding Officer was Wing Commander Keith Bolitho DFC who had been a Catalina pilot during the war against the Japanese in the SW Pacific.

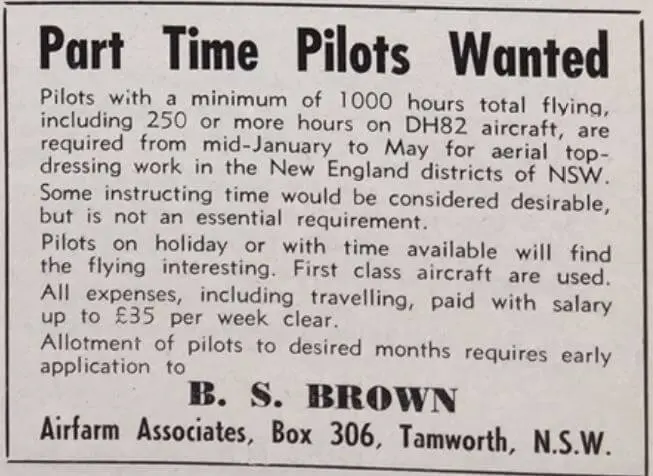

Around October 1955, a Tamworth based crop-dusting operator, Air Farm Associates, advertised in the Sydney Morning Herald for part time pilots qualified on Tiger Moths for crop dusting duties. Tours of duty were to be two weeks. As some RAAF flying instructors at Uranquinty held Commercial Pilot licences as well as being qualified on Tiger Moths and Wirraways they met the minimum hours on type for the job

Air Farm paid for pilots to travel from Sydney to Tamworth and return at the end of the short term Agreement. The pay was good although I cannot recall the exact amount. I think it was around 35 pounds sterling per week.

Two of our instructors, Flying Officers John Green and Tom Larkey took two weeks recreation leave in November 1955 and did crop dusting in Tiger Moths VH-BUM and BDF. Both flew about 80 hours in that period and arrived back at Uranquinty considerably richer. I applied to Air Farm in November 1955 and started my work period in December 1955. Basil Brown, the founder of East West Airlines was the manager of Air Farm Associates at that time.

I was given Tiger Moth VH-BUM and told to ferry it to a property near Wollam, not far from Armidale where another pilot was waiting to show me the ropes so to speak. My aircraft had seen better days. It was dirty, smelly and I was shocked to see it had no fabric aft of the rear cockpit although at least it had fabric on the rudder, tailplane and elevators. After the superb serviceability and immaculate appearance of RAAF Tiger Moths, I realised the yawning gap between RAAF maintained aircraft and general aviation.

It was only after I got airborne from Tamworth and realised I had to cross a mountain range that I noticed the compass was covered with phosphate dust which I had to wipe clean in flight. I doubted if the compass had been swung for years. On arrival at ETA I was unable to pin-point the crop-dusting strip marked on my map. I was too embarrassed to return to Tamworth. It was then I spotted a farm house next to a large field.

Setting up the Tiger Moth for a precautionary search, I did several low runs over the field to check for obstacles. It looked OK so I did a short field landing close to the farm house. Then walked to the house and knocked on the door. A kindly lady opened the door and I asked her for directions to the crop duster airstrip I knew was somewhere around. She asked where my car was.

I said I don’t have a car but I had an aeroplane in her field. She seemed quite unfazed and gave me directions. 15 minutes later I spotted an airstrip among some trees. There was a Tiger Moth on the ground as well as a truck and a ute.

That was good enough for me. I had always been a poor navigator and this only proved I hadn’t improved despite now being a qualified Grade C RAAF flying instructor. I was met by George Hite, a very experienced crop-duster who had flown Liberator bombers against the Japanese.

For the next two weeks George was my mentor as we flew from farm to farm. He was a lovely bloke and we got on so well. I flew 43 hours in that two week stretch. With summer density altitudes around 6000 feet in the Armidale general area and loads of 450 lbs in the front seat hopper, the Tiger Moth really struggled to maintain height. Full throttle and full back trim was needed to hold straight and level.

On my very first flight I had dropped my load of superphosphate at 200 feet along a ridge and hurriedly returned to the airstrip where the farmer had his truck ready to pour another load of super phosphate into the hopper. I was adept at short field landings and even though there were no brakes on Tiger Moths I pulled up right on the parking stop. The engine was kept running as the hopper was filled from an elephant’s trunk on the lorry. There was a shout from the farmer whose face was red with anger.

He pointed at the ground beneath the Tiger Moth and from the rear cockpit I could see a pile of white powder building up between the undercarriage. It was then I realised I had forgotten to close the bomb bay doors, aka the hopper exit door, after I had dropped the load over the ridge five minutes ago.

The farmer gave me a shovel and demanded I shovel the spilt phosphate back into the hopper. I switched off the engine and was about to tell him to get stuffed when I realised my mentor Bill Hite was already on short final in his Tiger Moth and I was blocking his taxi path. I swallowed my pride and got to work with the shovel with the farmer breathing down my neck. Being an RAAF officer, no one had ever spoken to me in such an insulting manner. But there was no escaping I had stuffed up and had to wear the loss of face.

George Hite was laughing his head off and after he explained to the irate farmer I was new at the job, things calmed down.

Two weeks later I was back at Uranquinty a few dollars richer in the bank account. Then in March 1956 I was off to Tamworth once again. The CO was mystified by the comings and goings of some of his instructors but as we were all taking approved recreation leave he chose to keep quiet but to keep his ear to the ground.

From 26 March to 6 April 1956 I flew flat out averaging between six to eight hours flying each day. All of which were to ag airstrips like Wollam, Walcha, and Jogla in the general country around Armidale. One of the pilots was a New Zealander called Bob Taylor. He was a short cocky character but he sure knew how to fly and make quick turn-arounds. He could lap me after ten turn-arounds and set out he could fly better than any RAAF trained pilot. He may have been right of course but we got on well despite his banter. I wore RAAF issue fur lined flying boots and flying goggles and gloves some of the time.

Bob was envious of my flying boots so at the end of my tour I gave him my RAAF boots and goggles as a gift. I had a feeling we would not meet again as by now the Commanding Officer was asking serious questions about our disappearances off base.

I had flown a total of 150 crop dusting flying hours before the CO threatened to court martial anyone who went crop dusting again. What broke the straw that broke the camel’s back with Wing Commander Bolitho, who was normally a genial senior officer, was the case of Flight Sergeant Ted Dillon who was one of the flying instructors. Ted was a fighter pilot on Meteors before undertaking the CFS instructors course. He was a quiet friendly man. While playing football at Uranquinty, Ted had hurt his foot which now had plaster of Paris around it. He was given three weeks sick leave. He decided to go crop dusting with Air Farm. He hacked off the plaster of Paris. While flying a Tiger Moth, he had an accident and damaged his good foot.

On his arrival back at Uranquinty questions were asked by the medical section about the second incident and what happened to the original plaster of Paris.

That is when the Commanding Officer stepped in and banned flying instructors from taking second jobs. I was relieved in one way as the crop dusting was dangerous work and the long hours on duty with hardly a day off to recuperate led to constant fatigue; especially as sometimes we were living in a caravan.

It was inevitable that fatalities would occur. Some months after my last flight with Air Farm, George Hite was flying an FU4 Fletcher crop duster aircraft near Armidale. It was approaching evening after a long day of crop dusting. He took off towards the setting sun and flew into a deadwood tree and was killed. Fatigue was considered a contributory factor and it was speculated he never saw the tree because he was blinded by the sun.

Then on 27 September 1958 in Tiger Moth ZK-ATL (New Zealand registration) Bob Taylor took off from an airstrip at Tangoio Bluff, Hawker Bay, NZ and his aircraft was never seen again.

Meanwhile Flight Sergeant Ted Dillon had been posted from Uranquinty to RAAF Base Point Cook where he instructed on Wirraways. During a solo practice dive bombing sortie at the Werribee bombing range, Ted was pulling out of his dive when one wing broke off. The Wirraway crashed and Ted was killed.

While I enjoyed crop dusting initially as something different to pure instructing, I could see why under some conditions it could be a dangerous game. The real danger was fatigue; particularly when flying was started at 0600 to take advantage of cooler and calm conditions. Sharing a caravan was not conducive to a good night’s rest particularly if the other occupant snored. In those days any flight time limitations were frequently disregarded in order to get the crop dusting completed and moving to another farm to start all over again. If an engine had rough running, we had to change our own spark plugs – always in a hurry. If spark plugs didn’t fix the rough running, the decision had to be made to fly the sick aircraft back to Tamworth over the mountains and hope to not have a forced landing on the way.

I was relieved when the CO pulled the plug on our crop dusting ventures. I was newly married and while the extra money earned was gladly banked for the proverbial rainy day, it was tempting to disregard flight safety norms just to make extra money. After two weeks of low altitude tension filled, ten hour days, I looked forward to going home to Uranquinty with its common sense RAAF discipline and the first class servicing by RAAF ground staff. “